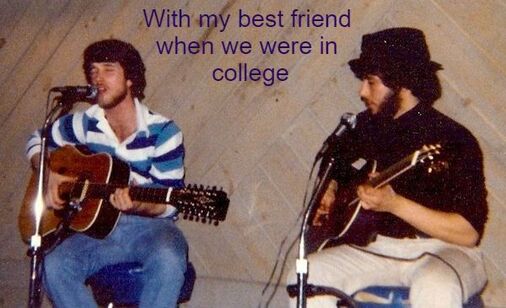

by David Brooks' piece in the The New York Times reflecting on "unexpected friendships, the social scientists tell us, turn out to be awesomely powerful" is great. https://lnkd.in/ex-28FnV The most powerful force in social mobility may be completely unintentional-having friends who are different than you. I am always humbled in some ways and inspired in others, with respect to my academic career, in the face of studies like this that suggest simple and obvious things are the key to success (how ever one defines it). I have learned that simply caring about students changes everything for the positive. This piece and the study it is based suggest that having a diverse friendship network is so very powerful. These simple very human things (friendships and caring) dramatically trump all the money spent in higher ed on student success and DEI initiatives. What is even worse, is that many universities, that have very diverse student bodies, have responded to changing demographics by implementing administrative/support programs to help students, while simultaneously increasing faculty teaching loads and course sizes to be more efficient. If caring by faculty members is as important as the data and my own personal anecdote shows, then having smaller classes where faculty can care is important, as well as the reality that smaller classes allow for group work that can form bonds between students from different backgrounds. Universities also often have programs aimed at students who are underrepresented, first generation, or financially insecure. Those programs don't usually include students from all kinds of backgrounds. Perhaps, though, our focus should be facilitating friendships across backgrounds-e.g., having bridge programs that include groups of students who are diverse in their socio-economic backgrounds. It doesn't take retaining that many students, who would otherwise drop out, to pay the costs. Finally- I was lucky when I was young in having a truly best friend whose economic circumstances were different than mine. But, as a high functioning Aspy, real friendships have not come easy in my life. Mr Brooks' piece made me think more about the challenges facing the many students with neurodiverse traits- such as not being able to read social cues very well. Universities have been an enigma to me in regard to broad-sense neurodiversity . I suspect that academe tends to attract people with neurodiverse traits because academe allows, even rewards, being independent (even a loner) and outside of a group, working with no dress codes, working intensely, sometimes alone, on a problem one is fascinated by, and with less pressure to be a good colleague (or even nice to people) than in many other professions. Yet, almost everything we do to try and create community in the academy is based on everyone being neurotypical. For example, we use all kinds of receptions to bring people together. For people on the spectrum like me who can't read social cues well, these are terrifying. I don't have an answer to this one. But, with a large portion of people having neurodiverse traits, this is one aspect of DEI that gets ignored other than for those on a more extreme end of the spectrum. And, with the formation of friendships across backgrounds being so important, perhaps this is something that should be thought about a bit more.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|