Update on this blog. I asked for people to tell me if I was wrong, and a colleague who had a greater understanding of the new budget model gently did. That person gave me access to data showing that I had a few misunderstandings of the new BOG budget model. I now understand that the new funding model exacerbates the budget issues associated with declining enrollment since we now lose (a lot) more money per undergraduate credit hour than we did in the last model (and gain or lose less per graduate credit our) when undergraduate sch declines. Of course, we will recover more quickly if we can create a reason for undergraduate students to enroll here. The other thing I learned, which is what I thought would be the case from past experiences, but it was such a focus of narratives that I heard I thought it played a lager role, is that the performance-based model is only at the margins, not the core of the new model. My colleague referred to it as a (the) red-herring, because the money involved is far less than the challenges caused by decreased credit hour production. I think my colleague confirmed, though, that the performance model is not comparing UNCG absolute numbers directly against UNC CH, but is based on marginal gains and losses from institutional norms. Although I still may be wrong about this, the new information did not change my opinion that UNCG is not inherently disadvantaged in the new budget model because of the students we serve. In the performance part of the model, we have room to make significant marginal gains. Rather, it seems we are disadvantaged because of how the model was implemented. Part of it is just bad "luck"; the new model took effect when UNCG's sch production was in free fall from declining numbers of new students and a post-covid retention drop. Usually, when funding models change drastically, quickly, in a way that really hurts units or schools, there is some period of "hold harmless" or for adjustments, I think the BoG helped to try and hold us a little bit harmless with an infusion of $3M in one time funding (this is from memory of provost's remarks) this academic year. I guess we either are not getting additional funds to help deal with the "bad luck timing" in the next fiscal year, or at least no one has said that we are that I have heard (and I may not be listening). I also think my opinion still holds that a major effect of the new budge model will be to incentivize UNC CH and NC State to increase in-state undergraduate sch production, if those schools want to maintain strong graduate programs. Some have interpreted the decrease per graduate sch as a "defunding" of graduate programs. Perhaps it is. But, I read it as just a new way to support graduate programs. Basically, if an institution wants strong graduate programs, and needs state appropriations to do so, increasing in-state undergraduate enrollment is the path towards having the funds. This creates an indirect problem for UNCG. If UNC CH and NC State significantly increase in-state undergraduate enrollment, then UNCG will lose prospective students to those schools because they are perceived as better (though the experience of many students here with faculty is outstanding- I would take it over what I have seen when I was at an elite private or two flag ship land grants). I still think the actions and narratives at UNCG right now, suggest to me that the budget issues have given some in senior administration the opportunity to do what they have wanted to do since they arrived: implement the strategy of changing the university from what it is, with a strong liberal arts and science core, to a 4-year "high-value" vocational tech model in areas like health, business and IT (and eSports)focused on the first job after graduation, in programs taught with fixed term faculty with high teaching loads, who are viewed as easily replaceable commodities, Perhaps that is incorrect. Yet, I think there is nothing in actions or narratives that would suggest otherwise. Or at least the data chosen for program review don't seem to me to point to much of any vision for the future. The importance that rpk puts on federal labor market data- does suggest the focus will be on the first job after graduation. There is research data in the mix, but grants and contract data don't necessarily say a lot about the impact of research. It does feel like a select set of data will be analyzed independent of any norms in our peer group with the hope that the data will define the vision. At least that is how I see it. Budget cuts are hard, but there are many ways to approach them. Our problems are serious, but don't seem yet to be existential. So, we still can have a vision other than just survive until tomorrow (and candidly, if survive until tomorrow is where we are, we probably should merge or close, fighting for survival of a public institution in the face of it not being needed seems wrong to me in some way in a State with so many good institutions). If we have a clear vision that is about finding a way to be the distinctive mix of select strong R2 research programs with transformational education, then that would lead to a different strategy to budget challenges, than a vision of transforming into a "new" kind of residential university focused on "high-value" vo tech programs in health, business, and IT, with a smattering of STEM. I came here because of how articulately the chancellor promoted the distinctive R2 university mission which so fits the campus culture and my values. Thus, I still hope that the chancellor believes that should still be the future goal. If so, that vision should drive how we approach budget challenges and the institutional and comparative data we examine. But, if the vision is something else, which seems clear to me from what I know about people, decisions on faculty retention and the program review process is targeted toward the sort of change akin, but not as severe, as to what is happening at New College in Florida. If so, then I hope leadership can be clear about it so we all know that is the vision that will direct the strategy for addressing the budget challenges and the university's future. My original blog is below- I stand corrected on the things I learned from my colleague (but I did not remove them from the blog so you can see where I was simply dead wrong). I still think that many of my opinions are still consistent with the data I have. Critical thinking is about changing a narrative when new information is provided and I am happy to do so. Let me end the update with a huge thank you to my colleague for correcting me on a serious misconception of one part of the budget model! And, keep the corrections coming,. The original blog of May 1. I was very glad to see the op-ed in Sunday's paper (4/30/2023) by a large cohort of former UNCG faculty who gave their careers to make UNCG an extraordinarily transformational institution. Their op-ed expressed concern about the UNC Board of Governor's new funding model. The model certainly has put people on edge. And, recent action/policies of the BoG around DEI, Faculty Grievances, Chancellor searches, etc, are simply scary to those of us faculty who believe in the power of higher education and of an organization that shares governance, with administrators having fiduciary responsibility and faculty having authority on curriculum and quality control of that curriculum. In sitting on the University's General Education Counsel this year, the faculty take quality control extremely seriously. It was inspiring to work with this group. I have some concerns, though, that the new budget model has been a red herring that has effectively diverted faculty attention from more important issues. Let me state now that I have no inside information. I have never talked with a member of the BOG. I have, though, searched the web earlier this year to try and find out more about the specifics of the budget model. Those data could be outdated. There could be much clearer data available to faculty in shared governance positions.. So, simply put, everything in this blog could be wrong. Thus, this is solely an opinion piece. My sense of the rationale for new performance funding model is not as nefarious as the narrative suggests. The increase in funding per undergraduate student, and decrease in funding per graduate student, seems to be a logical way to incentivize UNC Chapel Hill and NC State to enroll more in-state undergraduates to help subsidize their graduate programs. The ratio of undergraduates to graduate students at UNCG is relatively high, so it is possible (but I do not know) that the increased funding to undergraduates offsets the decrease to graduate students. UNCG is hurt by this part of the model because if UNC-CH and NC State enroll more undergraduates as a way to maintain their graduate programs, there will less NC students wanting to enroll at UNCG unless we offer something special. When the new budget model first came out, I believe it was run with 2020-2021 data and UNCG would have received a 1.4% increase in our budget- about in the middle of the pack of UNC schools. Our ratio of undergrads to grads is large (larger than UNC-CH), so the decrease in graduate funding, may be offset by increases in undergraduate funding. I don't know. Performance based funding models, generally should not be things that scare faculty. In essence, they incentive universities to get better- in this model better at student outcomes and lessening student debt. I doubt that any of us as faculty think we as a university should not get better every year at improving these student outcomes. We might argue that the metrics don't really define student outcomes, or capture other areas of excellence, but I can't argue against metrics like graduation rates, and reduced debt for students as outcomes that UNCG should get better at. The narrative has been that the new performance funding model pits UNCG against schools like UNC CH with direct comparisons. That is not how I understood the performance-based model. Like most states, I understood that the performance metrics would be weighted by institutional missions and targets, and driven by marginal improvements. If that is true, the model does no inherently disfavor UNCG. I am sure the downturn and enrollment and retention in the last two years would hurt us in the performance model, but would have hurt us in the old model, too. But, without knowing how performance based metrics are weighted by institution, I certainly can't tell how much the model would help or hurt us. In general, UNCG has a lot of room to improve those metrics, which means we theoretically would have a great chance of winning in the new model. I worry that new performance-based funding model is a red herring that leadership has relied upon keeping the spotlight off the new "vision" for UNCG. Given the data UNCG is using in program review such as the focus on faculty teaching productivity data rather than instructional costs; given the explicit requirement not to use comparative data like the Delaware Study in the review; given the focus on Department of Labor job growth data; given the lack of concern about excellent faculty leaving; and based on my experience with some members (not the Chancellor) of the senior administration, my uninformed opinion is that the budget challenges are being used as an opportunity to transform UNCG from a potentially high functioning, and transformational R2, into a 4 year university with many characteristics you might see in a vocational tech community college that focuses on health and business (and maybe some STEM). The conversation about faculty teaching loads leads me to think that the goal is to get to faculty that are full time teachers (4-4 or 5-5) loads, on fixed contracts, who are easily replaceable commodities. This strategy would ultimately raise sch/faculty much higher and reduce instructional cost/sch greatly. The university would have a long way to go to make that transition - but I would be surprised if that is not the intention. The question is whether students would enroll. I have to admit that I truly enjoyed working with the Chancellor when I was provost. We were completely sympatico with the vision of UNCG carving out what it means to be a university with distinctive research strengths with a strong and transformational role in undergraduate education. That vision seems to have disappeared. Rather, I see the vision leading us to a 4 year vocational school with non research, fixed term contract, faculty, ultimately sending UNCG into a death spiral because with each move toward that model, because fewer and fewer students will want to enroll. I mean community college financial models are the least stable financial model in public higher education. And, what would we offer in health and business that would make us more attractive than other UNC schools.? I also have to say the budget challenges are real and I am glad I am not responsible for fixing them. Yet, I know that fixing them does not require the institution to fully reshape its vision and transform into something that makes conservative anti-higher education people happy, and I don't think that approach has really worked anywhere. I may be completely wrong. I am always happy to eat my words. Although my interaction with the chancellor around my termination as provost causes me deep animosity toward him as a human being, I truly believed in his vision of what UNCG could become. And, I hope he can up his engagement and reinvigorate that vision. We are experiencing true budget challenges. But, my experience in higher ed tells me that these budget challenges do not have to change the fundamental vision that drew me to UNCG and that the Chancellor expressed so well when I was recruited here. So, it might surprise people that I state "Chancellor Gilliam- we really need you now!"

0 Comments

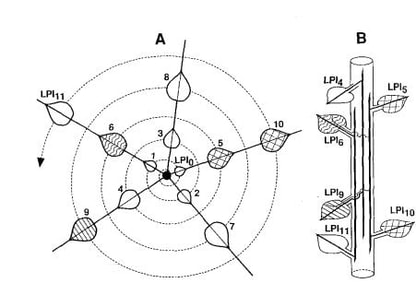

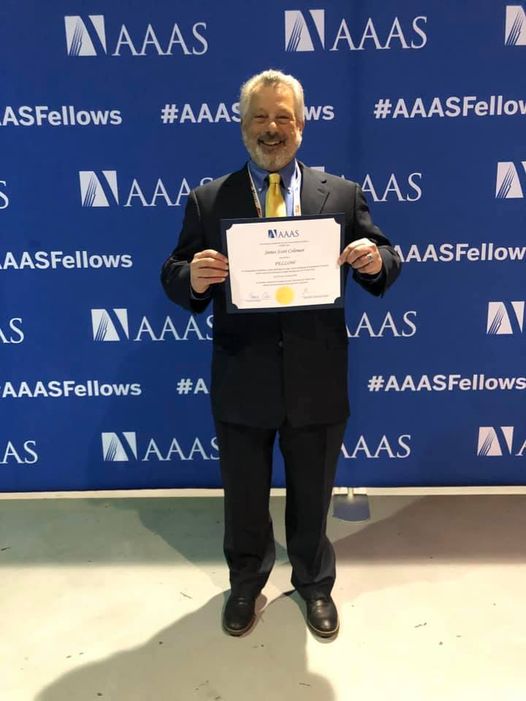

I had a special day today. The PR arm of the College of Arts and Sciences wanted to highlight me as one of a few professors in social media posts around our May 5 commencement. They also filmed me having a discussion with 12 graduating undergrads about their experience at UNCG and with me. To say the hour long conversation was profoundly fun and meaningful to me, would be a ridiculous underestimate. A few of the students had participated in undergraduate research with me- one saying in the conversation that a course in plant physiological ecology where they had to read two scientific papers each week, and the research they did my lab, took them from a somewhat lost student, to someone with tremendous focus on science, particularly conservation of marine animals. One of the other students in the conversation is working with five other students on a tobacco project. The first time I have used tobacco as a model system in 20 years. So, today I celebrate organismal biology, model systems, tobacco plants and eastern cottonwood just for the fun of it-. I am so excited to work with Tobacco again (after 20 years) with undergraduates. The tobacco plant pictured above is almost ready for the experiment! This pilot experiment is looking at whether the preference and performance of an insect herbivore feeding on tobacco plants grown in microplastic amended soils or controls. Unfortunately, I underestimated the time it would take for tobacco plants to grow, so the students are frustrated. But, they got to find a cool topic, amended soil with microplastics, designed and built plant-insect cages from PVC and netting that would have cost five times more to buy, transplanted seedlings and kept them alive. Students will finish the pilot experiment this summer. To digress for a second, I was at a seminar the other day where the opening slide showed a progression from genes, to populations to ecosystems that defined the topic. As a plant physiological ecologist, my heart sank that organisms weren't in the progression. That reminded me of the collaborative work of developmental plant anatomists with plant physiologists who took years, but brilliantly tied together the form and function of eastern cottonwood plants which allowed me to conduct a pretty fun PhD thesis and beyond. Also, tobacco is such a cool plant to work with for similar reasons. This blog post discusses some of my favorite papers using tobacco and eastern cottonwood as model systems that never got the traction they deserved in the scientific community. The work described below represents two out of five research areas my lab was focused on before becoming an administrator. Tobacco and Cottonwood My first paper, and my only single authored paper ever, was the result of a question on my PhD candidacy exam at Yale from Clive Jones, Bill Smith, John Gordon, Charles Remington and Mike Montgomery that related to my thesis using cottonwood as a model system. It was titled, Leaf development and leaf stress: increased susceptibility associated with sink-source transition. The project was based on a fully funded NSF grant I wrote with Clive. The group of friendly inquisitors asked to me look at the relationship between leaf development and susceptibility of leaves to insects and pathogens. A couple of hundred hours in the library (does anyone remember living in the stacks?), and a few hundred references, later I produced an answer that suggested that there was a window of time during leaf development associated with the sink source transition where susceptibility to specialist insects and pathogens peaked. And, that window was due to a balance of several characteristics including secondary compounds, size, toughness, nitrogen level, starch/sugar levels and was consistent across a wide range of organisms. That led to a cool paper that has recently found more interest from others. I didn't do so well on the other question they asked me, but they concluded that none of them could have answered it any better. They thought my answer to the leaf development and susceptibility to consumers was excellent, and they couldn't; argue with the funded NSF grant, and I was admitted to candidacy. One paper that I loved was led by then graduate student, and now Professor at Missouri State University (Alexander Wait;), "Chrysomela scripta, Plagiodera versicolora (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), and Trichoplusia ni (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Track Specific Leaf Developmental Stages" (https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-31.5.836) where we grew tobacco (and eastern cottonwood) in sand, and were able to control the relative growth rate, of plants by providing exponentially increasing nutrients daily at the rate of the RGR we wanted. And, were able to produce plants that had leaves reaching full expansion on the stem at different leaf positions. The results supported our hypothesis that specialist insects carefully tracked leaf developmental stage (and the point of sink-source transition) independent of RGR, independent of leaf position and independent of nutrient supply. It was such a cool study. I think, unfortunately, we published it in Environmental Entomology and it hasn't been read as much as it might have. A follow up paper on how closely insects track leaf development stage, in this case tracking the feeding behavior of aphids on cottonwoods, and carefully correlating that behavior with biochemical leaf characteristics was done by former PhD Graduate Student Georgiana Gould.. She showed in the paper "Variation in Eastern Cottonwood (Populus deltoides Bartr.) phloem sap content and toughness due to leaf Development may affect feeding site Selection behavior of the aphid, Chaitophorous populicola Thomas (Homoptera: Aphididae). " The aphid seemed to track leaf development to avoid mature leaves and to preferably feed on rapidly expanding leaves. Concentrations of the amino acids GABA and aspartic acid, as well as the phenolic glycoside salicin, differ in leaves of different developmental stages and may be used by the aphid to determine the age of leaves to feed upon. Another favorite paper is, "Why it matters were ion a leaf a folivore feeds " was conducted with a wonderful undergraduate, Soren Leonard (https://www.linkedin.com/in/a-soren-leonard-4316b344/). This paper (doi.org/10.1007/BF00328818) was based on the fact that the tip of leaves stop expanding well before the base of leaves. We hypothesized that given how leaves develop and expand, herbivores feeding on the base of the leaf would appear to have eaten much more tissue than those that feed on the tip of the leaf. And that amount of area lost from a leaf would be dramatically different if herbivores fed on the base vs. tip of an expanding leaf, which could lead to reductions in plant performance. We tested this hypothesis by taking the same area of leaf tissue from the tip or base of mature and expanding tobacco leaves. We found that removing area from the base of an expanding leaf created over twice the amount of visible damage than occurred on the tip of an expanding leaf. Furthermore, damage to the base of an expanding leaf resulted in nearly a 40% reduction in the final leaf area, resulting in a 35% reduction in the number and mass of fruits produced. .Some implications of this study could be extraordinarily important in assessing the amount of leaf area eaten at a whole plant, plant population and/or ecosystem level. For example if we had tried to estimate the amount of leaf area consumed by herbivores by the size of the hole from the base of an expanding leaf, we would conclude that herbivores removed 16.6 cm 2 even though only 3.9 cm 2 was actually removed. On the other hand, if we estimated the reduction in overall leaf area simply from the size of the final hole in a leaf, we might conclude that leaf area was reduced by 16.6 cm 2 when, in fact, damage to the base of the leaf resulted in over a 180 cm 2 reduction in the area of that leaf. (over ten fold). This really could have created large errors in data assessing the amount of herbivory or loss of leaf area due to herbivores in agricultural or forest ecosystems. Although I think this is a simple paper, I also felt that its results were really important for scaling from leaf development to ecosystems. However, it is hard to measure where an herbivore eats on a leaf in the field. Despite the fact I think this paper was a really important paper (and almost immediately accepted by Oecologia- a great journal for this work), the rest of the world did not- it has a really low citation rate relative to other less interesting papers I have written with students or colleagues. And, in discussing with scientists who try to assess the amount of leaf area that herbivores remove, or the affect of herbivory on ultimate leaf area, despite the 4 fold mistake in leaf area eaten, and the 10 fold mistake in leaf area reduction, they felt these data were simply an annoyance and would just unnecessarily complicate their work and the narrative of their findings. C'est la vie. There was another paper my group published using tobacco that was also an extraordinarily cool paper. My lab was interested in the ecological and evolutionary physiology of heat shock proteins and why, given their role in thermotolerance, were low molecular weight heat shock proteins only induced by stress and not constitutively produced (that we later demonstrated protect PSII during heat stress). Because of other work that had been done, we thought it might be possible that one leaf could be heat stressed on a plant and send a volatile signal in the air or a chemical signal through the vasculature to induce the heat stress response in other leaves. Molecular heat shock protein biologists, at the time, thought we were crazy, because they believed that cells only induced HSP production when they were directly stressed. Bill Hamilton a former undergraduate and PhD student (with Sam McNaughton and me) and now professor and chair of biology at Washington and Lee tested this idea using tobacco- again because the relationships between form and function that had put together by others in the paper " Heat-shock proteins are induced in unstressed leaves of Nicotiana attenuata when distant leaves are stressed. " https://doi.org/10.2307/2657048 Much to our delight, we discovered that a systemic induction of heat-shock proteins (Hsps) occurred in response to the treatment of a leaf with heat shock, mechanical damage, or exogenous application of methyl jasmonate (MJ). All treatments increased the abundance of members of the 70-kD Hsp (Hsp70) family and induced synthesis of one or more of the small Hsps (sHsp) (16–23 kD) in both treated and untreated leaves. Those results provided the first evidence that Hsps can be systemically induced in plants and suggest that systemic induction of Hsps may be important in pre-adapting leaves to stress. Why you ask?, Although we never tested this in the field, one could hypothesize, that, for example, leaves on the eastern side of plant may experience increased temperatures before those on the western side of the plant and that systemic induction might be valuable in inducing thermotolerance before the western leaves were in direct sunlight. Again, this very simple and cool experiment that kind of shattered a paradigm at the time that cells only induce greater production of HSPs if they are directly stressed. Nonetheless, not many people cared. A short trip into the ecological and evolutionary ecology of heat shock proteins Bill, myself, and a great post doc in my lab, Scott Heckathorn, professor at the University of Toledo, found this experiment really cool, and in the early 2000s it was kind of fun to find a result inconsistent with a molecular paradigm at the time. On a side note, my lab's work with heat shock proteins was originally aimed at linking molecular and ecological approaches to understand whether their where resource costs that prevented plants from just making them all of the time (and we showed that there could be) which led to me receiving an NSF (Presidential) Young Investigator Award. A paper with Scott and Dick Hallberg (a heat shock protein biologist of note working in yeast systems) "Heat shock proteins and thermotolerance: Linking ecological and molecular perspectives," described that perspective. And, we publishes numerous papers on this topic. But, sometimes our work became the subject of ridicule because of not doing the sort of mechanistic work that molecular biologists expected. So, we were forced (and that ended up being a good thing) to get better at molecular approaches to the HSP work in order to have our ecological/evolutionary work accepted. That culminated when Scott worked with Craig Downs, Tom Sharkey and me find a result that was something I would have never predicted/imagined being done in my lab- we were the first lab to demonstrate a molecular function for how plant low molecular weight heat shock proteins protect photosystem II during heat stress (doi.org/10.1104/pp.116.1.439). Who da thunk that? Back to cottonwoods Returning from the digression, the tobacco and cottonwood studies were related to NSF and the Andrew Mellon Foundation support. And, these projects were great fun because how fun it is to work with students. It is just a bummer that what was exciting to us (or at least me) did not resonate much with other scientists. But, I am really proud of the work these students did and the potential significance of the work. One other study conducted by an undergraduate that drew on the form and function work of the special people I alluded to above but didn't name- Philip R. Larson, Jud Isebrands and Richard E Dickson- who connected the form and functional development of cottonwood probably better than any other plant species. In their work they mapped the vasculature of cottonwood trees and related the vascular connections (and flow of water of and sugar) to the phyllotaxy of leaves. Leaves in cottonwood, develop at the same angle from each other and after a few spins (depending how fast they grow) their leaves vertically align. And, that alignment is always consistent with the Fibonacci series (see figure below). Nature loves symmetry. In most of the plants we worked on the phyllotaxy was 2/5 meaning that every that after 2 spins around the stem, every fifth leaf would align, and every third leaf would be most distant from the 5th leaf. Not surprisingly the strength of vascular connections was strongest between every 5th leaf. And the fifth leave after two spins was least connected to the third leaf. In the paper "Plant vasculature controls the distribution of systemically induced defense against an herbivore," Clive Jones, Robert Hopper (undergrad), Vera Krischik and I tested whether the vascular connections between cottonwood leaves could predict the strength of an induced defensive response in other leaves when one leaf was damaged. The paper showed that mechanical damage to single leaves resulted in systemic induced resistance (SIR) in non-adjacent, orthostichous leaves (vertically aligned on the stem) with direct vascular connections, both up and down the shoot; but no SIR in adjacent, non-orthostichous leaves with less direct vascular connections. The showed the control that plant vasculature exerts over signal distribution following wounding and might be useful in predicting SIR patterns, explain variation in the distribution of SIR, and relate this ecologically important phenomenon to biochemical processes of systemic gene expression and biochemical resistance mechanisms. This paper received more citations and much more attention. But, it never would have happened with the dedication to connecting plant form and function that inspired Larson, Isebrands and Dickson. Clive, Vera an I tried to integrate and conceptually model how plant form and function could link to new models of thinking about how the interaction between plants and insects and plants and pathogens can be interpreted from a greater understanding of plant-form and function and of herbivore and pathogen characteristics in three synthetic papers, A Phytocentric Perspective of Phytochemical Induction by Herbivores. In: D. Tallamy and M. Raupp (eds.). 1991 edited volume Phytochemical Induction by Herbivores. J. Wiley and Sons. pp. 3-45; Plant Stress and Insect Herbivory: Toward an Integrated Perspective. In: H.A. Mooney, W.E. Winner and E.J. Pell (eds.) Integrated Responses of Plants to Environmental Stress. Academic Press, NY. pp. 249-282 and in one of the best papers I ever wrote but almost nobody read, Phytocentric and Exploiter Perspectives of Phytopathology. Advances in Plant Pathology 8: 149-195. ISBN: 012033710X, 9780120337101. My grand synthesis (with Clive Jones) attempted to link plant form and function, plant phenology, evolutionary characteristics of insects and pathogens to describe the evolution of insect and pathogen communities on various plants, and specific traits that would be present in specialized insects and pathogens. It was the best paper I ever wrote, Leaf Ontogeny, Plant Phenology, and Plant Growth Habit: Toward a General Theory of Resource Exploitation by Herbivores and Pathogens. But, it was rejected by the American Naturalist with one very positive review (from Sir John Lawton, my academic grandfather- you have to admit it is pretty cool to have a British Knight as a grandfather) and one negative review. After leaving it and stupidly never resubmitting because I decided to move on to new things when I started as an assistant professor, I am back to it again. I have had a few scientists in the field read that paper recently and they all strongly encouraged me to get it up to date and resubmit. I am working with undergraduates on that now. I don't know why I procrastinated so much on the work I am proudest of. Science is funny that way. So, here is to Tobacco and cottonwood- both great model systems for organismal biology. Here's to a hope that the amazing understanding we have gained at the genome level doesn't make organismal biology obsolete. And here the hope that the new undergraduates in my lab with find a joy of working with tobacco that is not related to smoking. A short synopsis of the stuff that got more attention (and not): The other three main research areas (and two peripheral areas) consuming my life and accounting for a large number of citations are: 1) understanding the role of ontogenetic drift in plant traits in understanding the function of phenotypic plasticity with Kelly McConnaughay (and several of her students) and David Ackerly- the area of science where most of my citations are. (we started with a synthesis piece, Interpreting phenotypic variation in plants) and a symposium that David and I organized with some other amazing people, produced a nice paper that still gets read quite a bit, The evolution of plant ecophysiological traits: Recent advances and future directions; (2) Another area was global change ecology (around $20million in funding)where my work is cited frequently - example Nature paper here of a large team project in the Mojave Desert.. And the third area is another area that boomeranged on me. Twenty years ago I worked with Mae Gustin (and Mae's graduate student Jody Erickson), Steve Lindbergh and Dale Johnson on a project trying to understand the flux of mercury in ecosystems, where we published a kind of seminal paper in mercury flux (using aspen-- close enough to cottonwood for comfort), "Accumulation of atmospheric mercury by forest foliage ". This came back around when I returned to the faculty at UNCG in 2021 and inherited three grants from Martin Tsui, who moved to Hong Kong, looking at mercury flux in response to different silvicultural practices used to restore loblolly pine plantations to longleaf pine ecosystems. Oh, and then there is my short stint with radishes in Hal Mooney's group- another one of my best papers that barely anyone read came from my time in Hal's lab Anthropogenic stress and natural selection: Variability in radish biomass accumulation increases with increasing SO2 dose. I also had a blast working with Sam McNaughton as as his mentee and colleague when I was an assistant professor at Syracuse, and our students including Bill and Scott, Bryan Wilsey, Michele Giovannini, Ben Tracy, Kevin Williams, Doug Frank, Greg Hartvigsen and Stephanie Moses on interactions of grasses (and other plants) with herbivores. I am particularly proud of a conceptual/synthesis paper that Scott, Sam and I wrote on C4 Plants and Herbivory. And, Greg did a really interesting paper with Alexander and I on tri-trophic interactions as a result of resource availability to cottonwood saplings. Brian wrote some really interesting papers on global change and grasses with Sam and I-- a topic for another blog about the story of my carbon dioxide work. Writing about Sam just reminded me that during the seven years I was at Syracuse University (I was tenured and promoted there). I declined every offer, every year, to go to the Serengeti with Sam and his team. That is near or on the top of the list of stupid decisions in my life. I remember the days of cottonwood and tobacco (and radish and Serengeti grasses) fondly. And, I hope future days will also make me nostalgic before I die. Some other day I'll blog about our much more appreciated work regarding allometry/phenotypic plasticity in plant traits, global change biology, and mercury biogeochemistry. Below is a diagram of a 2/5 phyllotaxy of a cottonwood sapling. The shadings relate to the experiment. People actually hand drew these figures back then-- and it wasn't me. I can barely draw a straight line.  For those of you who had the misfortune of reading my post titled "It's time for time," I appreciate you. That post was kind of mis-titled, as if I was a were a headline writer for a tabloid, where the title had little to do with the blog. The post was largely about the joy of the academic rhythm, with a three paragraph digression about time as quoted below. "I have a new passion this semester: I am starting an imaginary activist group aimed at ending the practice of unnecessary meetings, and another one focused on fighting society's oppression of the value of time- I think that time is really sick of not being valued--and I worry what will what will happen if time goes on strike. I am hoping at one point the university will sign a new infinitely long contract with time, providing equity in its compensation with space and money. My imaginary group has a catchy slogan. "It's time for Time". Besides fighting for equity for time relative to space and money, we will fight to stamp out hurtful phrases such as "killing time", "wasting time" ,"crunch time", "do hard time", "got no time", "in less than no time", "it's payback time", "living on borrowed time:, "lose track of time", "the last time" "the race against time", "out of time", etc." This post is a follow up. To say it mildly and sadly, my revolution to protect time is failing. The first question you should be asking is that if I find time to be so scarce and valuable, then why in the hell am I writing a blog? Good question! I can only respond that writing on a blog, and maybe, if I am lucky, having 2 other people read it, is cathartic in its own way and makes me more productive. It's kind of like taking a laxative when you are constipated and feeling cleansed afterwards. I wrote this new blog because protecting time has made me feel guilty. From the time I was a undergraduate student in 1982 until now, I was willing to work 18 hours or more a day and worked both weekend days. As an Assistant and Associate Professor, I volunteered for everything- from making phone calls to prospective students (Syracuse University was in an enrollment crisis when I started), to playing a lead role in Syracuse's MLK celebration (which at that time was perhaps the biggest of any campus. filling the floor of the Carrier dome). As an administrator, the weekends were often the only time to get work done. During my phase as a Ph.D. student, I regularly blocked off time for exercise, but other than that it was all work and little play.. But, once I became a postdoc, especially with an advisor who would drive around at night just to see if the lights were on in the lab, I gave up protecting time. It has been that way ever since. Weekends were to get things done or to do weekend work-related activities,. Evenings were for doing work. Downtime was only available when I just got too exhausted, if there were house chores, or if the Steelers or Penguins were in the playoff hunt.. It has taken me 40 years to figure out that my time is not infinite and free. This is paradoxical because in my first administrative position back in 1997, I worked in a soft-money research institute where time, indeed, was equal to money. For example, if I wanted faculty members to come to a meeting, or do anything that was not related to their grants and contracts, I had to find a fund to charge their time. Most of my colleagues in universities gave me a funny look on their face and would say "WTF?". But, it was true. As an administrator, the State of Nevada covered my salary to run my the unit (though I covered half of it from grants), so I did not have the conundrum of violating the terms of grants and contracts to work all of the time on the "hard" part of my salary in addition to my grant funded work. This year, for the first time in 40 years, I have put a wall around Saturday. I spend most of the day with my wife, though I let myself work for a few hours in the morning. I put a wall around Saturday because: 1) Although not a practicing Jew, Saturday is our Sabbath and I am trying to find more spiritual meaning now; and 2) The real reason: My wife has much of Sunday booked. Having Saturday walled off for us has made me more productive at work and has helped strengthen my marriage. dah. Sunday-Friday UNCG owns me for usually around 75-80 hours during this semester. Sunday, Mon, Tues, and Wed are usually 14-18 hours on campus either in classes, prepping for classes, grading for classes, working my lab, or in my office engaging with students in person or digitally. and performing my duties as Graduate Program Director, member of the Gen Ed Council and a member of the Sustainability program's advising council. Thursday and Friday are usually 8-10 hours each. These are the longest hours I have worked in my career even as an assistant professor with 5 active grants (and who viewed by job as 100% teaching; 100% research; and 100% service) as well as VP,R, Dean and Provost. When I was a senior administrator, I was usually one of the first people in the office in the morning and the last to leave. To digress for a moment, an old family friend, and former dean and university president, told me recently in response to my saying I was tired because of working 80 hours a week, "you still have 88 more hours to work each week." Believe it, or not, that was a pep talk. This is probably the response I will get to this post from campus leaders. I don't mind my hours now, because they are spent mostly on things that reward me with energy, i.e., engaging with the 230 students I teach this semester. I don't want to ease up on that engagement, because that is the most rewarding activity that gets me up in the morning. But, getting home at between midnight and 2:00 AM four days a week does gets old. Here's my problem. Despite this level of effort, I am feeling extraordinarily guilty and frustrated about not having more time to give. In the last week or two, I have been encouraged to spend 8 hours in an "open space" meeting during the busiest time of the semester (the week before and during finals) and just before a major IT switch will occur that will require a lot of time on my end) so that Arts and Sciences and Biology faculty are represented, not because of being passionate about the theme of the meeting. Open Space Technology meetings are meant to only include people that are passionate about the theme. The Open Space "rule" is whoever chooses to attend are the right people- I am not in that group. Additionally, I have been encouraged to give up a big chunk of time on two Saturdays for undergraduate recruitment days (I care about this-- UNCG needs students an faculty can help- if these were on Sunday I would most certainly volunteer); attending training sessions on mental health and anti-bias (I am already certified in mental health first aid, and I can' even count the number of times I have done anti-bias training;) to attend a plethora of various seminars, particularly ones about student success and DEI,. To nominate faculty, staff and students for like 10 competitions for awards and review internal proposals for small amounts of money. And, then there are many recommendation letters for students. In total these non-core activity requests would come close to adding up to somewhere between a half to a full extra 40 hour week during the last five weeks of the semester. Oh, and then there is the invite for the 3 hour university commencement. In 25 years in admin-- every university I was employed at worked hard to have graduation ceremonies never be more than 1.5-2hours maximum. That is another story. When I was a provost and dean, I enjoyed the time on stage shaking hands (as dean I would go to 7-9 ceremonies over two days of graduation)- it flew by. But, after several thousand shakes, my hand did hurt a bit. I felt so sorry, for the families, and friends who really just wanted some pomp and circumstance, maybe a funny or profound graduation speech (rare), then to get to watch their student walk across the stage (with lots of hooting and hollering and pictures) having to sit there for 1.5-2 hours. And, I felt worse for the students who were generally bored to tears with the speeches, the honorary degrees, and having to listen to the chancellor or president talk about the accomplishments of 5 of the several thousand graduates, all of whom felt their story was also compelling. I can imagine how they might feel after 3 hours. When I was at the University of Missouri, we did have a 3 hour ceremony for graduate students, and at Rice we had a 3 hour ceremony on the Rice lawn with temperatures in the 90s and the humidity near 90%. These were not fun. Fortunately, a new graduate dean came in and shortened the graduate ceremony at the University Missouri to 1.5 hours. I don't think anything significant was lost with the reduction of 90 minutes. It is amazing what fewer speeches and speedier hooding can do. I really look forward to our much shorter graduate recognition ceremony in biology in May, 2023 and hope our students and families will have the energy to come after the 3 hour campus gig. I really look forward to just after the Biology ceremony, where I get to say farewell, get a hug from as many of the students I know as possible, and honestly tell their parents, friends and families how special their graduate is to me. That just can't be done at the big ceremony. And, my 62 year old back can't handle sitting in a crowded uncomfortable seat for three hours. I suspect the grandparents of some of our graduates may feel similarly. Sorry, although that seemed like a digression, but I feel guilty for not going to the 3 hour ceremony, too. This is a good Segway back to the theme of the post... The guilt I have now comes from understanding how important the Saturday events are, particularly recruiting students, but feeling like protecting my one day a week is a mental health necessity. This makes me feel like I am letting my department head down (who I am grateful for every day) by not showing leadership as a full professor in volunteering my time for these events and other activities. The frustration comes from a few things. Mostly, I am frustrated by the philosophy of most universities that time is an infinite and free resource for faculty and professional staff (a philosophy I probably had as an administrator-- though I was much more aware of how hard faculty worked than my senior administrative colleagues). I am a little frustrated that all of these events, including the requirement for curricular advising, are not officially in my workload (though all faculty in my department do these things). I am most frustrated, because each of the numerous events, advising meetings, seminars, and nominating individuals for award competitions, etc. are either important and/or worthwhile. Each of these is, by itself is doable (accept for the 8 hour retreat)). But, in aggregate, just thinking about all of them gets me exhausted and makes my head hurt. I hate feeling guilty for doing something I should have been doing for 40 years: walling off one day a week to recharge and be with my family. I am a cultural Jew, so the guilt gene is almost always overexpressed, making me acclimated to its effects most of the time. Methinks, though, the current sense of guilt has passed the threshold of effectiveness of that acclimation and I hate feeling that way. So, I am back where I started. I wish it were "time for time" to be valued as I indicated in the previous blog: "I have a new passion this semester: I am starting an imaginary activist group aimed at ending the practice of unnecessary meetings, and another one focused on fighting society's oppression of the value of time- I think that time is really sick of not being valued--and I worry what will what will happen if time goes on strike. I am hoping at one point the university will sign a new infinitely long contract with time, providing equity in its compensation with space and money. My imaginary group has a catchy slogan. "It's time for Time". Besides fighting for equity for time relative to space and money, we will fight to stamp out hurtful phrases such as "killing time", "wasting time" ,"crunch time", "do hard time", "got no time", "in less than no time", "it's payback time", "living on borrowed time:, "lose track of time", "the last time" "the race against time", "out of time", etc." I am sad and feel defeated to write that I have failed my imaginary activist group. Time is being less valued now than it was even back in August when I wrote the first blog. Maybe time will never have its time to be in equity with money and space. I am scared it will remain the oppressed resource in modern human societies. I wish time was viewed as precious in our culture, but as the Stones sing, "you can't always get what you want" Let me end with an apology to time and a plea to time: Dear time, Please do not go strike. I mean, evolution gets me excited, but without you, it has no meaning. And, if evolution goes away, I don't know what we are left with except for timeless black holes. Below this introduction is an email from Michael Daly from rpk Group to questions I submitted on the feedback form. These answers confirmed my worst fears about the project. The answer that was most alarming to me is the answer to the question (bolded and highlighted) about the rationale for metrics. I mean, I can't imagine writing a research proposal that indicated I am going to measure two dozen metrics but I can't really say exactly what we will learn from them but know that all of them are equally important. None of the answers were very informative. Some of them are articulated verbatim on the FAQ on the UNCG site. But, I understand that my questions were ones that Michael could not go into detail on.